Deep Dive: What Happened on October 24th, 2017?

Rouge waves, Lake Superior, and other stories

Lake Superior is a big lake. It’s the largest lake in the world by surface area, at 350 miles east to west, and 160 miles north to south. The Lake has an estimated 2,800 miles of shoreline.

There are a lot of “big” lakes in the world. If you aren’t familiar with Lake Superior and the Great Lakes it’s easy to underestimate Lake Superior’s size. The word “lake” itself lends to images of calm summery days and docks, not 729 foot long ships being swallowed by waves.

If you know the Lake, you know Lake Superior isn’t a lake, not really. It’s a sea. And on October 24th, 2017, that sea kicked up one of the worst storms in it’s recorded history.

Largest Recorded Wave in Lake History:

On this day in 2017, Lake Superior produced the largest recorded wave on a Great Lake, with a short period wave clocking a massive 29 feet offshore of Marquette, Michigan.

Note: short period refers to the time between wave peaks. Because Lake Superior is smaller than an ocean, and fresh water is less dense than saltwater, wave period are shorter. A short period 29 foot wave is going to not only be large, but also incredibly steep. Most sources I found indicated that short period means less than 10 seconds between wave crests.

Checking out waves during west gales at the Apostle Islands Sea Caves.

Lake Superior is a large enough, cold enough body of water to alter and create it’s own weather patterns; in the winter the Lake insulates, keeping the shoreline area just a little warmer. In the summer the opposite; on many summer days it might be 90 degrees and sunny four miles from the Lake, but down by the water a chilly 60 and foggy. The cooling effects of Lake Superior also effect weather, fueling electrical storms in the summer and massive winter storms that sink ships.

There are two factors that lead to those house-sized Lake Superior waves— in order to have large waves you have to first have wind. Then, you have to have a distance of open water for that wind to work over to create waves; this is called fetch. For example, fetches on Lake Superior can exceed 200-300 miles.

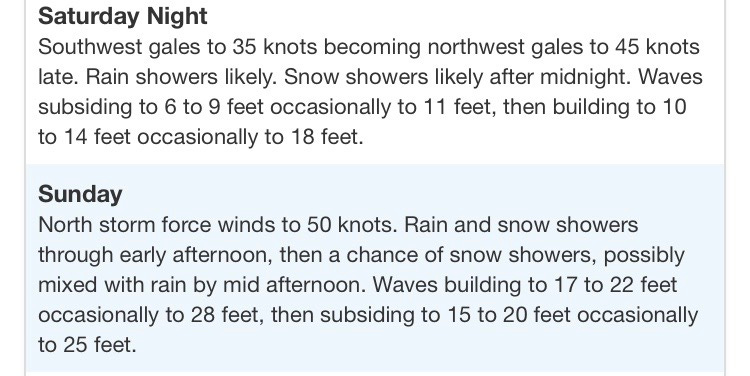

In general on Lake Superior, sustained windspeed around 20 knots (nautical miles per hour) will start to produce large and hazardous waves for small crafts. At wind speeds around 30 knots, you have a Lake Superior Gale, and will see wave forecasts start to near 15-20 feet.

Storm force winds (see marine forecast above, October 28th 2020) begin around 48 knots. When people say “a winter storm” on Lake Superior, they are generally referring to storm force winds. Storm force winds is about what it takes to get waves near 30 feet on Lake Superior.

Beyond storm force is hurricane force, or wind speeds greater than 64 knots. Hurricane force winds are very occasionally seen on the Great Lakes, and notably reported around the time of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

A lot marine forecasts and wave height predictions are based on the Beaufort Scale, a general scale used to determine what the severity of wind and waves are out at sea. The Beaufort Scale is not an exact measurement, and wind acts differently on freshwater than salt water due to differences of density. If you’re looking to get a general sense of what wind speeds correlate to what damage/wave height, check out the Wikipedia page here.

On October 24th 2017 when the largest* Lake Superior wave was recorded, the storm on the Lake experienced bombogenesis, a rapid drop in atmospheric pressure leading to rapid intensification of a storm, producing intense wind speeds. Bombogenesis happens when a mass of warm air collides with a mass of cold air. Generally, this happens over large bodies of water like oceans. Occasionally, this happens over large freshwater seas like Lake Superior.

*I’m using largest and highest interchangeably, but technically largest would refer to volume of water, not height of the wave alone.

October 24th 2017:

October 24th, 2017 saw the largest recorded wave on Lake Superior. Near the shoreline, winds gusted to 60 mph.

Disclaimer: all linked footage was acquired by people who walked past the park closure at Presque Isle Park this day. I do not condone walking past closures as it is not only dangerous but tacky. That being said, the footage is useful for Lake Superior education purposes.

Along the shoreline not far from where that largest wave was recorded is Presque Isle Park of Marquette, sometimes called Black Rocks. On the 24th, it was a popular spot for photographers to watch the waves roll in off the Big Lake, ignoring the park closure for high wave risk. One photographer was able to capture some pretty incredible footage of the waves, and leave a little damp but ultimately unscathed.

Others had the same idea, but weren’t so lucky.

Photographer Jerry Mills witnessed and caught on camera a man out on the rocks posing for a picture, who was then swept off the rocks and into the Lake. Luckily and incredibly, the man was able to catch hold of a rock and haul himself out of the water.

Other couple out on the same rocks were even less lucky. Reports of a couple swept off of the rocks and into the water made it to the Coast Guard at 1:35 pm. At 2 pm, search and rescue efforts began for the couple, with the Coast Guard helicopter from Traverse City on its way. At the same time, USGS reported 25-30 foot waves smashing into Black Rocks.

Note: the initial call was made at 1:35pm. The Coast Guard helicopter arrived at 4:14pm. On Lake Superior and with all Coast Guard/wilderness rescues you are likely dealing with at least three hours from contact time until rescue begins. Account for this in your decision making/risk management.

By 9:20pm, search was suspended due to dangerous search conditions with 25-foot waves and 40 mph winds.

According to news reports from 2017, Black Rocks/Presque Isle was closed for safety concerns that day. So all footage of Black Rocks from that day was attained by walking past a park closure. By the time search efforts for the missing couple began, police announced anyone in Presque Isle Park could be arrested.

One month later, the missing man’s body was recovered. The body of his partner was never recovered.

Rouge Waves and the “Three Sisters”

It can be really hard to make safe judgement calls around big water, especially if you don’t know how big water behaves. With groups of photographers out on the rocks that day, it would’ve been really easy for the people swept off the rocks to get the impression that what they were doing is safe.

I think that is probably an easier mistake to make than we realize. A group can give the illusion of safety, and it’s easy to watch someone do something dangerous and get away with it, then assume that means it’s safe for you to do too. We’ve all done that in some way or another.

Still, never walk past a park closure for a photo, or any reason. Park closures are not only there for your own safety, but for the safety of the rescuers who have to go out after you, and for the long term preservation of the park.

Walking past a park closure is not only dangerous, but disrespectful. That being said, the punishment for being disrespectful should never be death.

Wave height from October 24th, 2017 screen grabbed from this MPR article.

The largest wave was recorded at 9:30am, and the call was made about the missing couple around 1:30pm.

What I am interested in is the spike where the largest wave is recorded. When you’re out watching waves, it’s important to note that waves vary in height. You might be watching 10 foot waves roll in and hit the cliffs but never wash over. Then, seemingly out of nowhere a 15 ft wave will wash over the cliff.

Or, more likely, you’ll see a set of three waves larger than all the rest. A 15 ft wave, followed by a 16 ft wave, followed by a 17 ft. Then it will subside back to 10-12 ft.

This is a well documented and recently scientifically confirmed phenomenon on Lake Superior. Rouge waves, including sets like the Three Sisters, are waves that are often double the size of the average wave height at a given time.

While a scientifically recognized phenomenon on the Great Lakes and beyond, we actually don’t know what exactly causes rouge waves. Theories include wave energy refracting off shoals and cliffs, or the wave energy from swell catching up with the dominant wave pattern and creating larger waves, or wave current, wind, and waves themselves opposing in a way that causes waves to shorten in frequency to the point they merge into one, much larger wave. For an excellent breakdown of rouge waves and the Three Sisters from a physics standpoint, watch this video.

So what does this mean for Lake Superior?

Rouge waves or Three Sisters sets on Lake Superior are generally not nearly as deadly as on oceans, where wave heights reach 30 ft regularly and rouge waves can be 90-100 ft or more in height.

For wave watchers like the group at Presque Isle on October 24th, 2017, it meant that even though they were observing 20 ft waves, the next set could be a deadly group of 30 ft waves.

With this in mind, if you’re out watching waves on Lake Superior take extra care to consider your potential escape routes in the event of flooding, remember that the wave height you see now might change with no warning, and never hop over a park closure for any reason, not even your YouTube channel.

For kayakers and other people practicing Lake Superior water sports, rouge wave possibilities are also important to keep in mind. At the Apostle Islands Sea Caves, a 12.8 ft wave was recorded when the average wave height was 6.1 ft. While this wave would probably qualify as a rebound wave, or a wave created by wave energy bouncing off a cliff and combining with an incoming wave, as well as a rouge wave, it’s still a good reminder that wave height on Lake Superior can change quickly and dramatically.

Before you let that scare you off the water, note that not many people are out kayaking in 6 ft waves to begin with, and if you’re out paddling on a calm day your changes of encountering a rouge wave are virtually zero aside from waves caused by sudden rockfall.

Em & I were out last March checking out the waves on the Breakwater. This was the spray from the largest wave of the day. While the wave looks close to Em in the photo, the closest of the spray was probably still a good 10 yards away. I was standing farther back with my lens at full focal length. This makes the background look both larger & closer than it is.

Edmund Fitzgerald and Rouge Waves:

While October 24th, 2017 holds the record for the largest recorded wave on Lake Superior, it’s important to note that bouys were not installed throughout the Great Lakes until 1979.

Notably, the Edmund Fitzgerald went down in 1975 off Whitefish Point, Michigan, two years before bouy data existed. Instead we have the reports from the Anderson, a ship that departed with and roughly followed the course of the Fitzgerald on November 10th, 1975, and reported hurricane force winds to 75 knots.

The most probable cause of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald according to the official Marine Accident Report, is that there was a “sudden massive flooding of the cargo hold due to the collapse of one or more hatch covers”.

South of Caribou Island, the Anderson reported 18-25 ft seas. While the cause of death of the Fitzgerald was almost definitely the sudden massive flooding of a hatch causing the ship to sink rapidly without a chance to radio for help (especially likely seeing as the captain’s last transmission was “we’re holding our own”), there are plenty of other theories about contributing factors.

The Three Sisters rouge wave phenomenon has been named as a possible cause of the sinking of the Fitzgerald. Given reports of the sea state at the time, the longstanding observations of mariners and anecdotal reports of the Three Sisters, accounts from Captain Cooper of the Anderson observing waves cresting over the pilothouse of the Anderson, some 35 ft above the waterline, it is completely plausible that a group of waves closer in height to 35 ft than 20 ft affected the Fitzgerald.

Lake Superior & Climate Change

Climate change in the Great Lakes has led to increased average water temperatures, added stress to fish species, and an increase in algal blooms, but it’s also likely contributed to increasing storm and wind events in the Great Lakes Region.

According to Great Lakes Now, average wind speeds on Lake Superior have been increasing “five percent each decade since 1980”. In the past eight years, we’ve seen three storm events that were previously only seen every 500-1000 years.

And it seems like we’ll only see more of these wind and storm events in the coming years. Lake Superior is warming faster than the average air temperature in the surrounding area, and the pattern of increasing storm and wind events is likely to continue with the rising temperatures.

While it’s unlikely with modern technology this will lead to a modern Edmund Fitzgerald, increased waves and wind will likely lead to shoreline erosion, damage to buildings, and more people swept off the rocks and piers.

Big takeaway?

It’s only going to get more rowdy on Lake Superior. I’m not going to tell you not to check out the waves, but pay attention to your surroundings.

If the wind is blowing, the waves are building. Whatever size wave you see now, a set of three double that size could roll in off the Lake with little to no warning. Be smart, and don’t be afraid to politely encourage others to be a little bit a little smarter too—

Or rather, don’t be afraid to share information to help someone make a more informed choice about their safety. I’m not here to judge people for making mistakes on Lake Superior. As you probably know, I’ve made some pretty big mistakes out there. But we don’t know what we don’t know, and I’m sure if those people had realized just how dangerous it was to be on those rocks, if they’d known about rouge waves on Lake Superior and how common they are, they probably wouldn’t have gone out there at all.

We can’t fault people for what they didn’t know. We can share information to stop things like this from happening again.