encounters with whales

field notes from San Juan Island

The laundromat is at the marina and overlooks the ocean. There are poppies in bloom, and a seal in the harbor below, and rows and rows of sailboats and yatchs with WASP-y men and their wives in pastels.

It’s nearly 12 dollars for a load of laundry, not including detergent. Island time indeed.

I chat with the older man who has come in to talk with me while I toss seawater damp clothes in the washer. He tells me he’s been on the island since the 70s, and shares his own kayaking stories. He tells me I should buy a beater sailboat and fix it up, and live out of the boat for a while, because delays are often endings.

When he leaves, he runs back to tell me quickly when to visit the market for the best baked goods. I thank him.

After, I sit alone in the laundry room and watch the sailboats bob up and down in the harbor. “It feels like there is so much I should tell you,” the man had said at one point. I thought that was strange.

Then I thought that maybe it wasn’t.

Here is what I have been up to since you last heard from me:

First, I drove across the country. Four long days— first from Two Harbors to Minneapolis. Minneapolis to Medora. Medora to Bozeman. Bozeman to Anacortes. To here.

Then, I did two weeks of guide training. This will be my fourth summer working as a sea kayaking guide, but my first summer working as a guide on the ocean, math not including last summer, where Andy, Ebba, and I spend a few months paddling the southern third of the Inside Passage, including the area I’ll be guiding this summer.

Guide training was hard in that it was time consuming and without real breaks. We rolled from learning about systems in the outfitter, to ACA training (American Canoe Association Training) which was easily one of the more intense on-water trainings I’ve done and super informative, then directly into our training overnight.

Then, after two straight weeks of training, Andy and I continued directly into guiding our first 5-day overnight trip. While Andy and I have both guided on overnight trips, paddled hundreds of miles together, and guided a few small day trips together, we’ve never actually guided an overnight trip together. It went really, really well and it’s awesome to have a co-guide who you not only completely trust on the water but who you can super easily express concerns or frustrations with— (hey, we need to have our group closer together, or I need more help with clean up, or let’s do it this way instead) and have them work with you to fix, and vice versa.

The hardest part of guiding longer trips is co-guiding. Everyone has a certain way they prefer to do things, different approaches to safety, and different approaches to what work they would like done when. If communication and expectation setting isn’t crystal-clear and done early, it’s super easy for small tension to build into a bigger issue.

Working with someone like Andy, who I already know well, have guided with, have 100% confidence in his paddling and rescue skills made co-guiding extremely smooth and easy.

We got back from that overnight trip yesterday. Today is my first real day off in a few weeks. Even so, while I’m off from kayaking, I’ve got writing and photography projects that need work. Not that I’m complaining. I work a lot to cobble together something that looks like a career, but I’ve got two jobs that I love completely. There’s nothing I’d rather be doing.

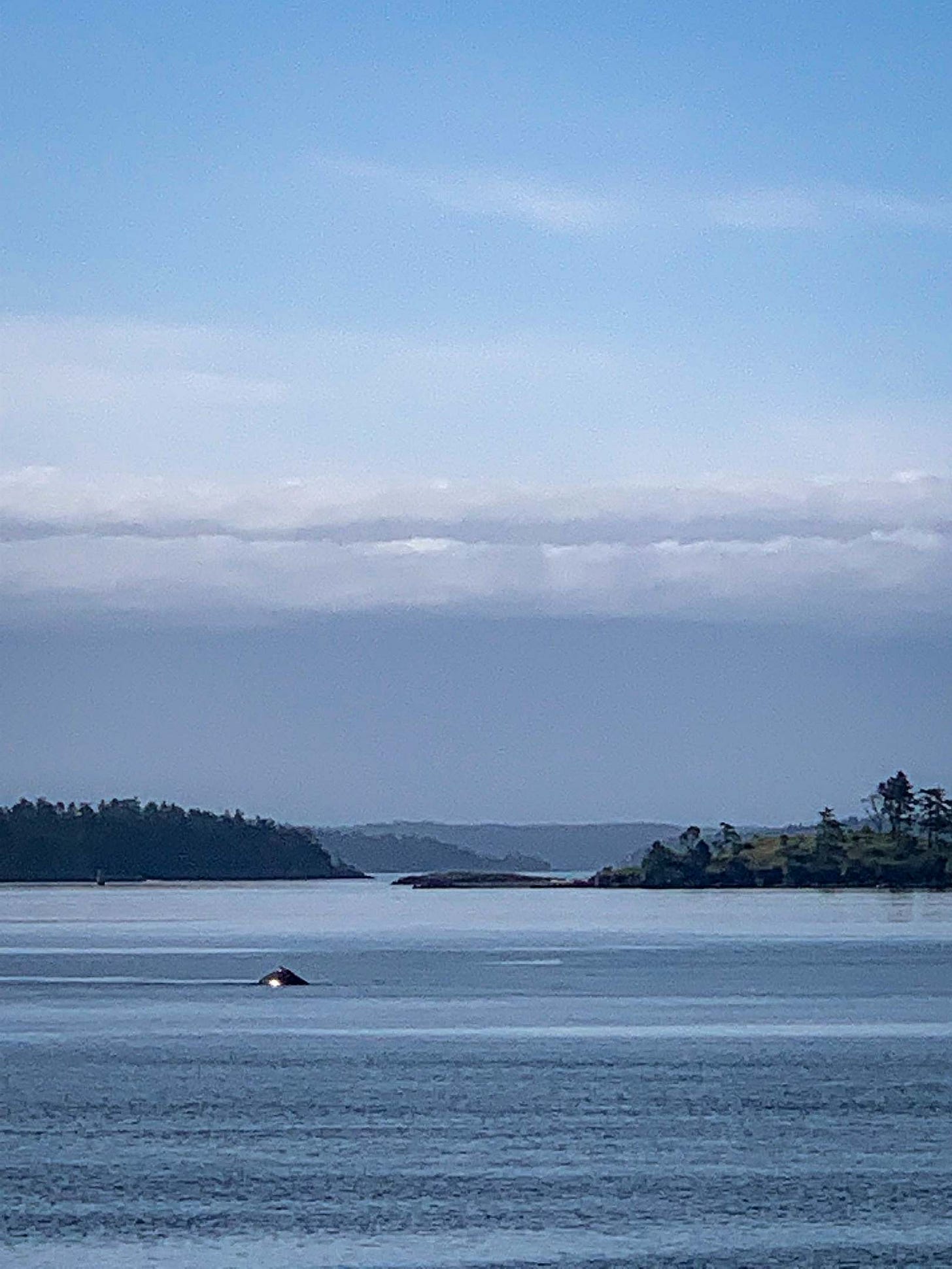

On Tuesday, we abandoned the boiling water on the stove to run to the shore and watch the whales, two humpbacks cruising down Spring Passage.

Last summer in the Redonda Islands, the blast of a lone humpback echoed off mountain sides and through the inlets so loud that I jumped, thinking it was a meteor hitting the water. A huge fluke, or tail, grew up from the water.

On Tuesday the pair of humpbacks was farther out, but nonetheless impressive. We walked the trail on Jones Island with the kids who were awake watching the pair head north to Canada.

“They’re huge,” one of the students said, eyes wide.

A group of thirty disenchanted high schoolers who were dragged out to kayak camp for five days, and while they didn’t love the paddling, or the salt, or the sunburn, or the boat lifting, the whales they did indeed love.

There is something startling and exciting about your first whale sighting— knowing that something that big could be right under the surface. For someone who didn’t grow up by the sea, it’s sort of fantastical.

Moreover though, whales are smart. Orcas are known to have names for each other and use language. They work cooperatively while hunting, and orca mothers will carry the bodies of their dead young for days in mourning— in the case of Tahlequah, a 20-year-old Orca who lost a calf, her relatives even helped her carry her dead calf while she mourned when she couldn’t herself. The Lummi Nation, or Lhaq'temish, Indigenous to the Salish Sea, have understood and treated Salish Sea orcas as family members since time immemorial.

Recommended read: What a Grieving Orca Tells us

It’s an intelligence you can sense when you encounter your first whale— the way they move, the sounds they make, the way they look at you. Encounters with whales are a tangible reminder that there is so much more to the earth than we see and understand— this planet is one we share.

Photos like this one are shot on iPhone and edited with my Adventure Presets for iPhone! These presets, or photo filters are compatible with the free version of Lightroom Mobile and designed to help brighten and enhance your adventure photos in just one click. This photo is edited with the preset “Forest Light🌲”. Use the code NEWSLETTER35 for 35% presets.

Updates & Other Readings:

Guest Writer Lea Cicchiello writes about distance hiking on a guided tour in the Italian Dolomites. The twist? The tour is conducted entirely in the Italian Language.

Distance Hiking the Italian Dolomites: Immersed in Nature… and Language

After our first visit to the Dolomites, my husband and I knew we would have to return. I searched for trips and found what looked like a great week of backpacking on the Alta Via 1, a high route in the eastern Dolomites. The trip would be with a guide and a group.

Wondering which Great Lakes summer vacation is right for you? Take the quiz below to learn which Great Lakes destination is perfect for you and your dirty Subaru!

QUIZ: what great lakes vacation should you take this summer?

The first blooms are on the trees here in the Upper Midwest and campsites are beginning to book up for the summer months, which means it’s time to figure out where you’re going to spend that long weekend you plan on taking in early August! Grab a pencil, paper, and a biggggg cup of coffee and settle in to find out what Great Lakes summer vacation destina…

If I could start over in my blogging/writing career, I would do it differently. Here’s why:

Are Influencers People? (the answer may surprise you:)

When I first started writing the idea of being seen wasn’t sickening because I didn’t really know what it meant. Little girls with abstract ideas of success and what it might mean to be a writer think of pretty scrawling script and candles that burn low, very Jane Austen, very Emily Bronte, very Mary Shelly Virginia Wolfe Zora Neale Hurston. Young women…