The first time I encountered J-pod, a family of 25 members of the Southern Resident orcas, was on day 15 of our 70-day paddling trip last summer.

We were headed north as we rounded a public park north of Nanaimo, British Columbia, a crowd of people gathered on the shore and called out to us, “Look! Behind you! They’re here!”

A several hundred yards out, massive black fins cut across the surface punctuated by whale spray as the orcas exhaled. They travelled at about four knots (nautical miles per hour), the same pace we paddled, headed north with us to Texada Island, the northern limit of the J-pod’s home waters.

In the evening while we pitched out tents we watched the orcas weave north through rocky islands while the sun set.

In 70 days on the water, we saw orcas just three times— that first time in the Strait of Georgia, a group Transient orcas at the municipal campground in Powell River, and the same pod of Transient orcas, a mother and her three children, just off our campsite in the Redonda Islands. We paddled with them just the one time in 70 days, and from a huge distance.

So when the marine biologist on my day trip of two people (her, and her husband) asked me what the odds of paddling with orcas up close were I answered honestly—

“Usually if you see orcas it is from a distance. In 70 days of paddling last summer, I saw orcas three times. That being said, they do come up close to shore, and there’s been a lot of orca activity in the area the past few days, so there’s a chance.”

I, like everyone on the Earth, wanted that magical paddling with the orcas experience. The reality is that the odds of paddling (legally) with orcas are slim to none. It is illegal to approach orcas even by kayak, and illegal to launch your kayak with orcas present. If you’re on the water and you see an orca in the distance, you’re required to stop paddling, stay close to shore, and raft up and wait for them to pass. The only way to paddle with the orcas is if they decide they’re paddling with you.

Speed boats have strict minimum approach distances, as do kayakers. A report by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife recommends all commercial and recreational vessels (including kayaks) keep a 1,000 yard distance from the Southern Resident orcas specifically. For kayakers, it’s pretty impossible to spot orcas from a distance of 1,000 yards, and while you can divert away from orcas, they can reach speeds of 35 miles per hour. A commercial kayak tour can maybe do three mph, but probably not.

The difference between the kayak and the speed boat when it comes to marine mammals is pretty substantial. In a kayak there’s no motor noise, and no chance for accidental propeller strike. You’re travelling slowly and you’re at eye level with the water. Generally, kayaking has a pretty low environmental impact when done consciously (ie, not dragging plastic boats depositing microplastics, being conscious of over-visitation, and behaving appropriately around marine mammals). There’s almost no way you could physically harm an orca from a kayak (like, without a harpoon).

An orca, on the other hand, could toss you and your kayak like a rag doll if it wanted. Don’t worry, it probably won’t— there are no reported attacks of orcas on kayakers.

Perhaps you’ve already heard about the orcas attacking boats recently off the Straits of Gibraltar. It’s speculated that White Gladis, the matriarch of her small pod who seems to be spearheading the attacks, may have been entangled in fishing line and some point and now has trauma around boats. White Gladis has been teaching the rest of her pod to take out the rudders of sailboats. In this region, the Iberian orca subpopulation is critically endangered with just 39 individuals, and has frequent contact with fishing and recreational vessels. There’s no real way to know for certain why these orcas have decided to target boats, but the continuation of the behavior poses a risk for orcas and humans alike.

Here in the Salish Sea, orca attacks are pretty much unheard of, despite orcas having ample trauma around boats. In 1970, a pod of orcas was herded into Penn Cove of Puget Sound driven by speed boats and bombs, then netted. Fifty-eight captured orcas were loaded into trucks and sold to marine parks around the world. In this orca capture, five orcas drowned including four calves trying to reunite with their captured mothers. The drowned baby orcas were cut open and loaded with rocks and anchors and sunk, to avoid being included in the official count. This event would later come to be known as the 1970 Penn Cove Capture.

According to Orca Network, reports from the Penn Cove Capture include “piercing, screaming vocalizations,” from orcas heard both above and below the water. It was an extremely violent event from which the Southern Resident orca population has not yet recovered.

Included in this capture was a small female orca Tokitae of the L25 matriline. Tokitae, or Lolita as she is sometimes known, is almost 60 years old today and the only current survivor of the Penn Cove Capture. She still exhibits calls that are unique to her pod, and has been living in the second-smallest whale tank in the world for the past 53 years. Plans have been announced to move Tokitae to a seaside marine sanitary in the Salish Sea, but there are definitely a host of concerns about moving her. Any animal in captivity for that long is likely to have trouble readjusting, and it’s extremely unlikely that she would be able to survive on her own in the ocean. On the other hand, she still has living relatives in the L pod, and after years not only in captivity but in subpar conditions, she deserves better than a tank.1

Despite the trauma of the Penn Cove Capture and subsequent losses, the orcas of the Salish Sea are not known for targeting boats, and certainly not kayaks. No, they won’t mistake you for a seal. Orcas are too smart for that.

In a kayak you’re at eye level, and you are not the apex predator anymore. There are no known attacks of orcas on kayakers— personally, I think that is because in the same way we recognize a little bit of ourselves in orcas, our own human intelligence and social structure, they recognize the same in us too.

J-pod, the orcas I first crossed paths with off Nanaimo last year, don’t eat marine mammals anyhow. As members of the Southern Resident orca population, they eat salmon. Southern Resident orca is a term referring to an ecotype of orca characterized by complex vocalizations, a fish diet, and a matrilineal social structure. Sons and daughters stay with their mothers for life, and the pods are generally organized around the oldest reproducing female. It wasn’t until the 1990s that fathers of orcas were deduced through paternity testing; male genetic input comes from a different pod, but a father will not join the pod of his offspring. The Southern Resident Orcas are made up of the J, K, and L pods, with the J-pod frequenting the waters off San Juan Island most often.

While Southern Resident orcas are most often and reliably seen in Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia, their range includes California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia as well.

The other ecotype of orca seen in the Salish Sea is Transient orcas, or Biggs2 orcas. West Coast Transient orcas include about 400 individuals, and are different from Resident orcas in that they hunt other marine mammals including seals, sea lions, and even occasionally juvenile minke or humpback whales. Contrary to as implied by the name, Transients are just as “resident” to the area as the Resident orcas. Transient orcas vocalize less than their Resident counterparts, likely due to the the advantage of silence when hunting marine mammals. Like Resident orcas, Transients are matrilineal, however unlike the Resident ecotype, mature female offspring will break off and start their own pod. Evidence suggests that Transients have been genetically distinct from other ecotypes of orcas for at least 750,000 years.

Both Transients and Resident orcas are regularly spotted in the Puget Sound/Salish Sea area. In general, the Southern Resident pod spends summers in Puget Sound and around the San Juan Islands, frequenting Haro Strait and the west side of San Juan Island, where most day kayaking trips in the area run.

Orcas are spotted with some regularity on trips on the West Side, most often at a pretty substantial distance.

It’s a big ocean, and the Southern Resident orcas numbering just 73 individuals, 74 if you count Tokitae in captivity, are few. Again, last summer in 70 days on the Salish Sea, I saw J-pod just once, Transient orcas twice, and one humpback. Paddling on San Juan Island is one of the best places in the world to see whales, but the odds of seeing orcas are still relatively low.

Moreover, the Southern Resident orcas are endangered; threats to food supply including declining salmon numbers, increased boat traffic, and warming ocean have effected their numbers, as well as the incredibly violent 1970 Penn Cove Capture and other captures in the same time period.

The plight of the Southern Resident orca has a little bit of popular culture mythos behind it. From Tokitae in captivity garnering global support for better living conditions, the Penn Cove Capture, to Tahlequah, the mother who carried her dead calf for 17 days in mourning with the help of her family, to Granny, a matriarch who lived to 105, the Southern Resident orcas have stories that are familiar to us and allow us to see a little bit of humanity in the orca, if not a little bit of the wild in ourselves.

The connection between man and orca is one the Lummi Nation (Lhaq'temish) have had for centuries. To the Lummi Nation, orcas are considered tribal members, people of the sea, and extremely akin to humans. The Lummi Nation has been instrumental in advocating for the safe return of captive orca Tokitae, or Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut in her Lummi name, to her home waters.

All this to say, while I knew going into the tour that there had been recent orca activity along our route, I tried to set expectations low. Keep your eyes on the horizon, watch for blows (orcas breathing) and fins, but don’t expect to paddle with the orcas, because that just doesn’t really happen, partially because if you see an orca, you are supposed to stop paddling pretty much immediately.

A trip of just two plus me, we cruised on an ebbing current much faster than usual, and right as we reached what I decided would be a good turnaround point I heard it, the telltale sign of a whale breathing and saw a black fin in the distance.

We watched from just a few yards offshore as one orca became three and they steadily moved closer. In the distance an orca breached, throwing itself high into the air and landing so loud it echoed across the water.

For about 20 minutes we watched them from a distance of about two or three football fields, maybe more, then they started to move in a little closer. We scooted back even closer to shore, then they were gone.

We waited a few minutes, and I debated having us hug the shore back to the beach for lunch, but they had to have gone somewhere, so I waited a little longer scanning the horizon, cautious of the rules about paddling while orcas were near.

Just a half a minute later they surfaced around us on all sides, six or so orcas a hundred yards to our left out in Haro Strait, three directly in front of us including a juvenile who leaped through the air, and several behind us. Another orca, larger than the leaping juvenile but still smaller than the largest ones, swam directly between us and shore less than a stones throw away.3

They were so close we could easily hear them speaking and smell their spray.

It was also at this point, when the orca swam between us and shore, that I started to feel just a touch nervous. Orcas are huge. Like I said, if an orca wanted to toss your kayak like a rag doll, it could. The logical part of my brain is not at all afraid of orcas. The less logical part of my brain was imagining a massive orca coming up from the depths teeth-first.

Lucky for us, we were not orca snacks. Instead, we heard the orcas and watched them for over an hour, at first from a distance and then suddenly and without warning up close. And it seems a little like they did the same with us— observed the kayakers from a decidedly safe distance, listen to our quiet vocalizations of “oh wow, that’s incredible”, and then moved on.

Ideally and legally, you stay at least 400 yards away from Southern Resident orcas, but I’m really not sure what I could’ve done differently. We didn’t approach, there was no way off the water once we saw them, we didn’t move at all while we could see them and we were lucky enough to have negligible current so we didn’t have to. Orcas can swim at 30 mph, and it would’ve been impossible to predict their path. When we first spotted them, they were far enough out that we weren’t even sure what we were looking at. We definitely maintained position and didn’t drift from our little spot just offshore— I made sure to consistently check that we weren’t drifting towards them. We weren’t particularly loud other than maybe a “wow!” when the first few breached, which might have been why they came over to check us out. It’s hard to say. Either way, if an orca pod decides they’re going to investigate you, there’s really not much say you have in the matter.

I had posted a video on Instagram of the encounter, but I ended up archiving (effectively deleting) it for a few reasons. The first is that while it was an incredible encounter and felt extremely close in person, it was still an iPhone video taken by someone actively guiding (ie, quality was not my priority) and the orcas are still far away and hard to see. It was the most incredible encounter anyone could possibly hope to have, but impossible to translate on a screen. The second reason is that people are protective (rightfully so) of the Southern Resident orca population. While I know I didn’t violate any marine mammal laws (and quadruple checked after because I’m kind of rule-conscious) and I know did the absolute best I could have to keep both the people with me and the orcas safe, other people don’t necessarily know that. Leaving the video up wasn’t worth any potential backlash or interrogation, especially from people who don’t know me, and the appropriate rhetoric around marine mammal protection on social media is something I’m still working on. It’s easy here, in a several thousand word post, to explain the intricacies of the Southern Resident orca population and interactions with them. It’s harder in a catchy video with limited words allowed in captions, and an even more limited attention span— there’s never any guarantee people are reading the disclaimer you’ve written.

Somehow on the same trip, we landed for a very quick lunch and spotted humpbacks breaching off the shore as soon as we landed. By the time we were ready to launch, the water was whale-free again and we cruised on a favorable current back to the put-in. We pulled up our kayaks and the orcas swam by one last time.

After the trip, I showered and drove back to the coast in hopes of seeing the orcas again. Though we were miles away, you could see the snow-capped cone of Mount Rainier seemingly growing straight out of the sea. Sure enough, just where I’d left them, the J-pod played in the eddies in currents below. The next morning they were gone, the infamous J-pod spotted somewhere far south of here.

other things I’ve been up to:

Earlier this week Andy & I visited Orcas Island! We’ve travelled together before, but up until that weekend literally every single trip we’ve taken together has been to see family, or an overnight kayaking trip, which I think says a lot about our priorities.

This trip we tried out “glamping”, did a few easy hikes, and enjoyed being tourists one island over.

thoughts on glamping

Glamping is totally foreign concept to me it turns out. In my head I thought glamping was going to be akin to car camping. I guess I sort of thought that anything that wasn’t backpacking and sleeping in a tiny tent was glamping adjacent.

I was totally wrong— it turns out glamping tents are just hotel rooms with canvas walls, all of the beauty and feel of being in the outdoors and near a fire pit but none of the dirt or work of actual camping. I used to joke that I didn’t understand who exactly glamping was for, like, just go camping? Turns out the answer is me, glamping is totally for me, not because I can’t hack it real camping but because I like my creature comforts like a bed and floor but also want my bonfire with a few.

visiting Moran State Park

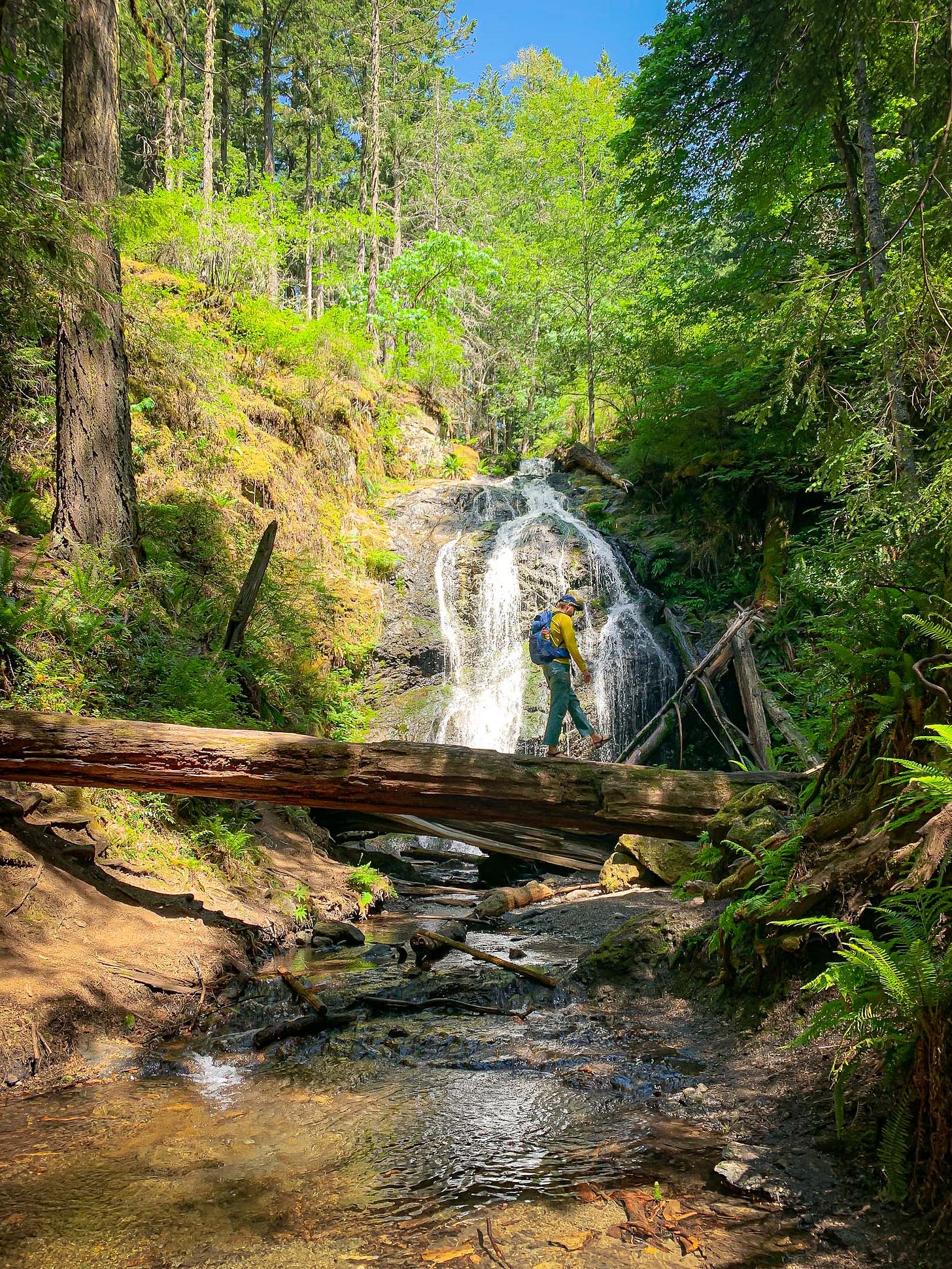

Part of our trip to Orcas Island was to check out the beautiful Moran State Park! Moran is tucked away on Orcas Island, an almost two hour drive + a ferry ride from Seattle, ripe with miles of hiking trails, island waterfalls, mountain lakes, and the impressive Mount Constitution.

We only hiked Mountain Lake and to Cascade Falls, but I’m hoping to get back out to some of the other trails and overlooks in the near future. Really a beautiful spot.

Reading Recommendations

A year ago on our 70-day trip, I picked up the book TIDES: the Science and Spirit of the Ocean by Jonathan White in a bookstore on Lopez Island. TIDES is both a narrative and an educational dive into how exactly the tides work, an adventure story and a useful guide.

I paddled with TIDES tucked away in my kayak from Lopez Island, WA, to Powell River, BC, where I dropped it in a community library for someone else to appreciate. This winter I regretted it— there were so many concepts I wanted to revisit, anecdotes I wanted to hear again. I thought about that book and regretted leaving it about twice a day, all winter. I hope whomever picked it up enjoys it as much as I do.

On Orcas earlier this week I went on a local bookstore quest to find myself a new copy of TIDES and was successful; I now own a fresh copy of TIDES and will be re-reading this summer. I also learned from the local bookstore in Eastsound that White, and Orcas Island local, passed away in April after a battle with brain cancer.

White was a wonderful writer, extremely skilled at blending science and personal writing. I highly recommend picking up a copy of TIDES, one of my favorite books I’ve read to date. You can visit White’s publications archive here for more of his work.

A few selected posts from our 70-day paddle trip last summer & more paddling stories:

North from Nanaimo

Five days ago I was ready to quit. It was cold and we were making slow progress. It seemed like things were constantly going wrong in an insurmountable way. The group dynamic was off, and it didn’t feel fixable. In high school, my cross country coach told us “you can do anything for ten minutes”. I think about that a lot— I thought about it on a miserabl…

sometimes you’re shit out of luck

It’s all fun and games until you’re stranded on a rock in the sea with persistent diarrhea from god knows what, slowly missing your carefully planned tidal window, desperately trying to stay hydrated so a bad shituation doesn’t become worse. CW: potty jokes, medical things, an existential crisis

Your Listicle Is Killer (no, literally it might kill someone)

The internet, Instagram, and Hell are all rife with the listicle, a pithy list saturated with links and keywords created for the sole purpose of raking in eyeballs. This week, popular paddling magazine Paddling Magazine put out article* 10 Reasons Fall is the Best Time to Paddle Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

To be clear the plan is not to return her to the open ocean with no support! At the very least, she’ll be getting a new and improved tank. At the best, the hope is to build a marine sanctuary for her on the ocean where she will be cared for by familiar trainers.

Bigg’s orcas as in Dr. Micheal Bigg who conducted the first orca survey on the west coast and figured out that you could identify individual orcas based on scars, scratches, dorsal fins, ect. While studying the Southern Resident population, Dr. Bigg was able to recognize a different type of orca coming in and out of the area separate from the Southern Residents and called them the Transients.

The real miracle of this trip is not just the orcas but that we had the ebb current on the way out, were magically at slack current for the entire orca encounter, then precisely when the current switched to flood, in our favor again, the orcas left for good leaving our path home and to lunch clear.

After a horribly stressful couple of weeks this post is what I didn’t know I needed. To escape for a moment with you and the whales was so calming. Thank you. It seems like you are enjoying life on the coast. While there are always ups and downs, I appreciate you sharing your moments with us 💛

Hi Maddy! Loved reading your post and the notion of how we see ourselves in whales. I'm a travel nurse and will be (back) in the Seattle area next week for a few months and now I'm even more ready. I also was thinking about planning a trip to Moran State Park--now I definitely will. Thanks for sharing your words. <3