“I think it’ll probably be fine?” I said, eyeing the storm cell in the distance over Lake Superior.

From the peak of Fantasia Overlook the storm looked far away, and radar info indicated it was tracking East. We’d get rained on, but probably not electrocuted.

We stalled on the peak, colors of fall bright below us and thunderhead alarmingly at eye level a few miles out. We’d almost definitely be fine to continue the extra mile on to Johnson Lake. With only two or three rumbles of thunder, no visible lightning, and the storm not technically tracking toward us, it seemed safe enough.

“I don’t know,” I shook my head. “We’re pretty high up. What do you think?”

Emily, my usual hiking partner, eyed the storm and our map. “We can always come back to Johnson Lake.”

Simple as that, it was decided. Rather than hike the extra two miles, we headed back to the car. Halfway down the mountain, a loud clap of thunder told us we’d probably made the right choice.

Emily and I usually run a tight ship when we’re outside. We pretty much always carry a topographical map for the area, always tell others where we’re going and when to expect us back, and we don’t hike in the dark without headlamps. We’ve both recently added safety whistles to our kits, and I carry a fully stocked first aid kit with a signaling mirror, and often a Garmin InReach. Overkill? Maybe.

But we’re on the same page about what is safe and what we’re comfortable with, which hasn’t always been the case for me in the wilderness.

Me on the cliffs at Fantasia Overlook. Shot a collaboration with Em.

If you’re interested in this hiking route, click here.

One of my essays got a Best of the Net nomination!

A while back, I wrote an essay about miscommunication and the outdoors, and why I don’t fish. Nick Adams Dies in a Diner was recently nominated for the Best of the Net anthology, which to me is a big deal!

Best of the Net highlights some of the best essays of the year. Publications select two essays in each category for a nomination from everything that publication published that year (I received a nomination from Pidgeonholes in the nonfiction category).

I’m incredibly honored to have this piece nominated. Nick Adams Dies in a Diner is something I wrote when I was 22, and just beginning to grapple with the strange differences in the way men and women seem to experience the outdoors and the implications of those differences.

Seeing it published last year was incredible enough; seeing it recognized beyond that is… it’s hard to explain how that feels. I wrote this piece about a failure of communication. One of the first people I shared it with was another man in the outdoor industry.

“It’s good…” he said. “I mean I can tell it is good, but I guess I don’t really get it. I think it just wasn’t written for someone like me.”

The act of writing is so intimate and vulnerable, and private; the act of sharing work comes with this horrible fear of being misunderstood. Coming to terms with the fact that my writing is not for men was hard in a strange way; like pouring your heart into words you think are clear but when someone you care about reads those words they fall on completely deaf ears.

Like they read a different story than the one that you wrote. Communication is scary, and has consequences.

Seeing this piece recognized sort of dispels all those fears perpetual misunderstanding and validates what I already knew; my writing isn’t made to help men understand what it’s like to be a woman in the outdoors. I write to help women and other people grappling with their relationship to their environment feel understood.

Mountains, Men

I recently shared excerpts of Deep Trouble on Isle Royale part one publicly on Instagram. I’m glad I did, because it’s an in progress piece I’m proud of and I think the final product is going to tell the story well.

Deep Trouble on Isle Royale is generally about what exactly happened to us last year on our Isle Royale trip (ie, how I got literal hypothermia on a 12 day sea kayaking expedition and what went wrong before and after), but more fundamentally it’s about what my experience as a woman has been in the outdoors and how being a woman in this space has influenced the choices I make. It’s about how those previous experiences outside primed that one. The story form Isle Royale is about leadership, and the way we sometimes try and use nature like a tool and it isn’t one, and it’s about the words we use and just how much trouble they can get us in.

Some of this essay is for paying subscribers only; this is because it’s a very personal story. It was hard to write; it’s been harder to share.

Like Nick Adams Dies in a Diner, this story deals with failures of communication. Like Nick Adams, this story isn’t necessarily written to resonate with every man.

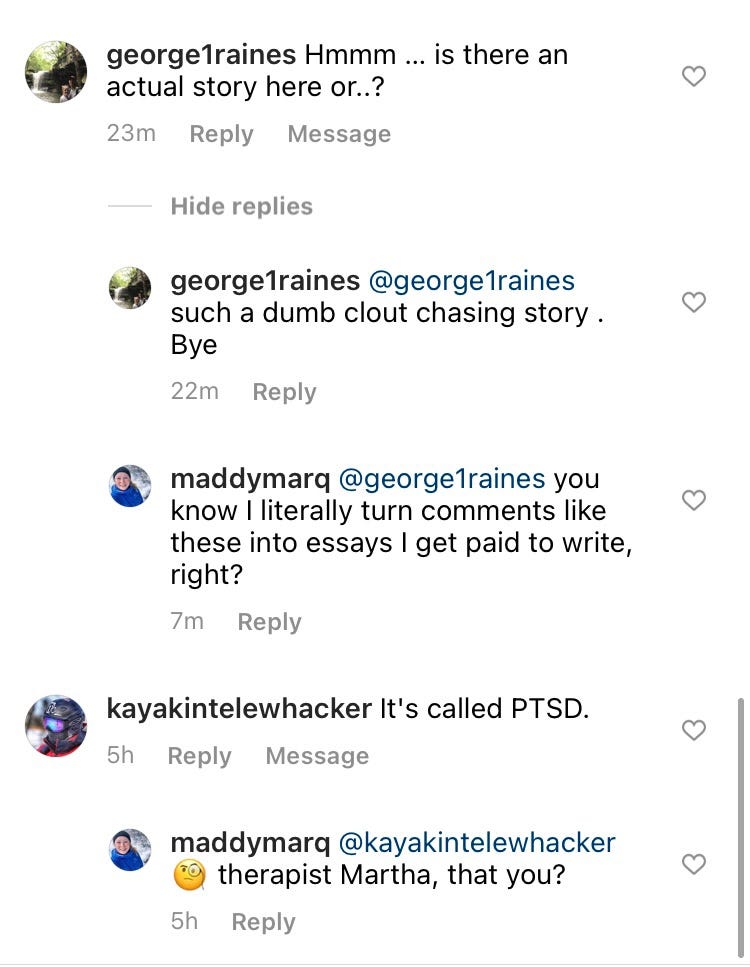

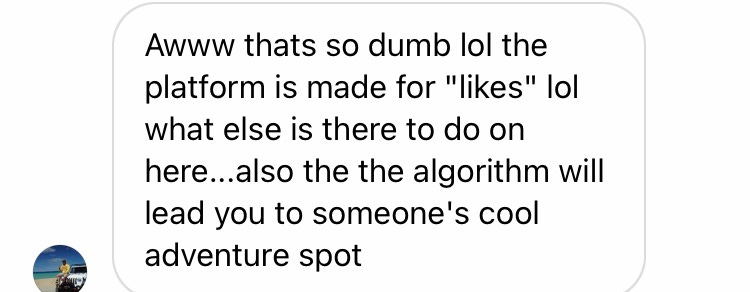

I have a lot to say about attitudes towards women in the kayaking community specifically, especially the online community, but I’ll let the last comment speak for itself.

Let’s circle back to George though.

George left a nasty comment on a piece about a woman’s experience in the outdoors. George is not the only one to behave this way. Some men are offended at the idea of outdoor writing that does not exist for them. Between Krakauer and Muir and all the tired others, outdoor writings and topics have largely been for white men. It’s easy to feel like a whole genre should belong to you when it has historically catered to your interests and experiences.

Men like George think “aw that’s dumb”. They don’t want this type of writing to exist, because the existence of such art and writing means that the outdoors themselves, a place deeply claimed and colonized by white men, is no longer for them alone.

It was, of course, never was for them alone. Think of the people who are enraged about sharing of outdoor locations, calling it “blowing up special spots” or “Instagram is bad because it gives away someone’s adventure spot”.

Here, it is the possessive case I am interested in; the idea of ownership.

When did we start talking about the woods like they were a thing that can be owned? Why do we (though it is largely white men who leave comments like these) feel ownership over a place, and feel that we should be able to shut others out of it?

George commented that my story about my experience on Isle Royale was dumb and clout chasing; the other sea kayaker felt the need to educate me on my own mental health in a condescending and demeaning way; the last commenter (on a different post) used the possessive case (“someone’s) to refer to land itself.

Once, a frustrated a 22-year-old version of me wrote this:

Somewhere in the soft green light of the forests of Northern Michigan, where trout spawn in the streams and blood flows in the lakes, Nick Adams and a thousand other anglers have written of women and land like they were both something that could be owned.

Comments are hard; we’re all the main characters of our own stories. This isn’t meant to be a men are terrible post; some of my best friends are very wonderful men.

But I do think there’s room for us all to learn from each other, and I do think more men need to hold space for outdoor writing that might not be for them, not only women writers, but more especially Indigenous writers, Black writers, and writers belonging to other marginalized groups with different experiences in the outdoors from the experience of a white man.

[Reccomendations: Tell My Horse, by Zora Neale Hurston. Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Deep Water Passage by Ann Linnea.]

Sharing your writing is hard, harder than writing it. It doesn’t always go how you planned. The toxic wasteland of social media is a natural fertilizer for deepening division, literally fueling hate and profiting off misunderstandings.

I want to leave you with a sliver of something hopeful:

On that same post sharing excerpts from Deep Trouble on Isle Royale, a different man shared a story about his own harrowing experience in the outdoors and his relationship to a mountain.

I won’t share his story, because it’s his own to tell, but I will share my response:

(Edited for clarity)

I’m sorry to hear that happened to you!

It’s interesting that you use words like “beat” and “win”— the crux of this whole piece, and a lot of my outdoor writing, is sort of that men and women tend to experience nature very differently on the level of the stories we tell about the outside. I have trouble relating to men and their stories because in those stories the outdoors are always viewed as a challenge or competition and in terms of success or failure; for me, and it seems a lot of my friends who are women, it’s more about the experience itself and less about winning or loosing. (I’m speaking generally, obviously not all men or women, but it is a pattern I’ve noticed). Because of that, I’ve never really felt like Superior beat me— I haven’t stopped paddling, and I still take on kinda gnarly trips. For me it was less about loosing, and more that I learned some very important things about leadership and my own communication, and failures of.

I can’t speak for your experience, but thank you for sharing it. It’s cliché to say “get back on the mountain”, so I won’t. But it might help to reframe the experience not as a loss, but just as what it was; another experience. Even when we climb a mountain successfully, we haven’t beaten it. And even when you fail to climb the mountain, that doesn’t have to mean it’s beaten you.

Thanks for reading!

If you want to read Deep Trouble on Isle Royale (part 2) you can subscribe to my paid reading list by clicking the button below.

Subscribing gives you access to exclusive essays (including those about Isle Royale), access to commenting, and makes it possible for me to keep the vast majority of my trail guides and resources free for everyone!